Issue #05

17 DECEMBER 2024

It didn’t happen what it was supposed to: since 2023, climate change has gone from a solid scientific finding-which some could nevertheless play deny with the public-to a dramatic direct experience in the daily lives of many, everywhere, incontrovertibly. But an adequate response is still slow to take shape.

In this globally worrying picture, the danger emerges ominously in our region as well. While the waters of our sea are the fastest warming in the world, the region as a whole has the second fastest rate of warming progression. Indeed, the average temperature in the Mediterranean compared to the pre-industrial era has increased by 1.5°C, and warming is proceeding 20 percent faster than the global average. A figure, this, that if not countered by mitigation actions could lead some areas to record increases of up to 2.2°C in 2040, and 3.8°C in 2100, with catastrophic consequences for a Mediterranean population that has grown exponentially in the meantime.

There will be destabilizing impacts. For example, it is predicted that our sea level could rise by 20 cm by 2050, which may seem small but would salinize the Nile delta, disrupting the livelihoods of millions of people; or an increase in the water-exposed population to 250 million. We must prepare for these and many other consequences. But to merely take the measure of such direct impacts is to fail to understand that a crucial stake is at stake: the identity and unity of Europe and a constructive relationship within the most natural sphere of internationalization of the Italian economy, the southern shore and beyond it Africa.

Looking at the planisphere, one realizes that the idea of Europe-as a continent in its own right-is an anomaly. Using the continent-demarcation criteria applied for all others, we should not exist: we are just a small appendage of Asia. Yet, we continue to feel like a separate continent, indeed perhaps-with that bit of conceit once called Eurocentrism-we feel like THE continent, the “old” continent! What sets us apart? A certain cultural, even physiognomic unity, a sense of community in diversity. Few question the roots of these uniquenesses that are not based in the ‘isolation of one’s territory, but some have: beginning with Montesquieu who saw European identity as a product of the climatic exception that has blessed Europe since the end of the last ice age, some 10,000 years ago.

If Montesquieu was right-and by contemporary criteria we can confirm that he was right-it means that the climate of Europe has played a decisive role in shaping our identity and defining our interests. The same applies to the southern shore of the Mediterranean, which, with its own marked identity dynamics is Africa without really being so. The southern shore of the Mediterranean also benefited from its own favorable climatic exceptionality that helped distinguish its identity from the rest of Africa. These two favorable exceptions were interconnected by the stabilizing action of the sea that we share, and they created the conditions for the agricultural revolution: the major social structuring from which the human organization into cultivated countryside and urban centers that is still ours began. It happened mostly around the Mediterranean-between Europe, Anatolia, Phoenicia-because a stable and predictable climate is essential for planning crops. However, this climate is changing. The stabilizing inertia of a vast body of water such as the Mediterranean no longer works if its waters store and release increasing doses of energy into the system that turns into chaos. This is not just a matter of winds and rains or even doctrinally anthropological: it is about economics, trade, and geopolitics. The deep foundations of our balances become unstable, and a destructive escalation of conflict is looming if we place ourselves in increasing competition in the face of new scarcities and uncertainties. This is a scenario that no one can afford. An impoverished and destabilized Mediterranean-well beyond regional concerns-is a global threat as three continents with all their interests converge there.

But if we look at all of this objectively, we find that the changing climate compels us to work together and can thus be turned into an unprecedented opportunity for just and sustainable growth and thus peace. Here in the high-risk Mediterranean, we are probably experimenting with the comprehensive approach to winning the climate battle: a simple recipe, together we can. Until now, the extreme diversity around our sea has led to fragmentation and too often to misunderstanding. But this diversity can turn into complementarity, a wealth of knowledge and resources so diverse that it is enough to mitigate and adapt for the benefit of all.

While the European Union wants to decarbonize, south of the shared sea there is huge solar potential, for example. In the North we need it; but even in the South, if its exploitation were only local there would not be enough market to finance its proper development. North of the Mediterranean is seeing accelerating desertification, but the phytogenetic resources-the plants and crops traditionally adapted to drier climates-and the millennia of experience on how to exploit them currently belong to the South. Will each of us keep what we have for ourselves? The climate challenge shows us that the path of constructive integration is the only one possible. Essential-but perhaps not intuitive in the uncertainty that awaits us and would instead presage renunciations-is, however, to understand that the opportunity for a new cycle of sustained-and finally balanced-economic expansion, because all participate for the benefit of all, and not renunciations, ensues. An expansion that, paradoxically, while we are trying to deal with climate gives us peace in a region where inequality has been a driver of conflict for millennia.

What will be the effects of the European Union’s CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) in the Mediterranean? Hard to predict today.

The CBAM will take effect from 2026 with a transitional phase. The mechanism will gradually impose a proportional tax on emissions of emission-intensive products such as aluminum, hydrogen, cement, electricity, fertilizer, and steel imported from third countries to the EU. This tax will be calibrated to equalize product costs among European producers, who are subject to carbon pricing mechanisms (EU ETS[1] ) that affect the final cost of production, versus non-EU producers, for whom there are no such regulatory restrictions with respect to GHG emissions in production processes.

This mechanism was designed to rebalance the risk of relocation of production to countries without emission constraints and, at the same time, steer demand toward ‘greener’ products. However, in the absence of mechanisms to encourage investment in ‘cleaner’ and more sustainable technologies and production processes, it could only result in a ‘barrier’ to access and economic development for Europe’s trading partners and an increase in the final cost of goods for European producers. Such an effect could isolate Europe and hinder the industrial transformation necessary for climate goals to be effectively achieved globally, not just in Europe. It is necessary, therefore, to take these consequences into account especially with respect to the ‘closest’ trading partners, such as those in North Africa, also in relation to the interconnectedness of value chains on a global scale.

Beyond the significant trade in petroleum products and gas[2] , France, Italy and Spain are among the top trade destinations for manufacturing in North African countries.

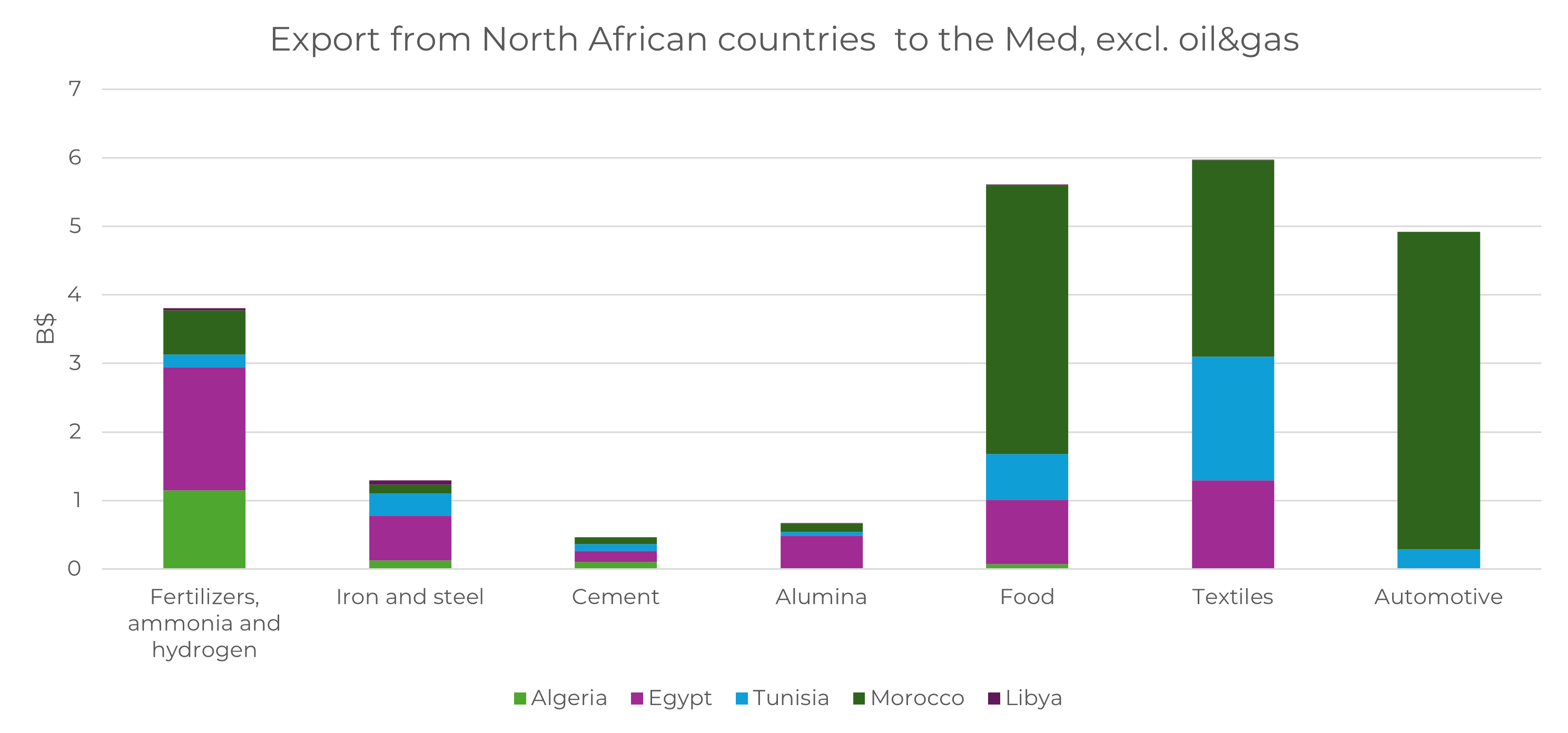

Looking at manufacturing sectors, the extent of trade between North Africa and Europe is shown in the figure below.

Manufacturing exports from North African countries to the northern shore of the Mediterranean [3]

Fertilizers and inorganic chemicals, including ammonia and hydrogen, reached $3.8 billion[4] . In this sector, Egypt exported 47 percent of the value, followed by Algeria with 30 percent. The steel sector reached about $1.3 billion, with Egypt exporting 50 percent and Tunisia 25 percent. Finally, aluminum and cement, ~$0.7 billion and ~$0.5 billion respectively, saw Egypt’s share of 74% and 34%.

Looking at the sectors not included in the CBAM but, nevertheless, subject or to be subject to the EU ETS from 2026 onward, the automotive sector (cars, tractors, trucks, and spare parts) reached about $5 billion, with Morocco standing out among the producing and exporting countries (94 percent). Furthermore, in 2022, the textile sector reached about $6 billion and sees a significant share of Morocco (48 percent), followed by Tunisia (30 percent) and Egypt (21 percent). Food exports reached $5.6 billion, with Morocco exporting 70 percent of the total value.

The main exports from France, Italy and Spain to North Africa, however, include cereals (France traded about $2.5 billion with Morocco and Algeria), machinery, mechanical equipment and related components.

From the data, the CBAM will affect the economies of North African countries in very different ways. By applying a carbon price to the above products, it will make these products more expensive for EU importers and likely less competitive with low-carbon alternatives unless current exporters put in place measures to decarbonize these productions or carbon pricing measures equivalent to those in Europe.

Among the Mediterranean countries, Algeria is perhaps the one most likely to be affected, which, incidentally, could affect Italy more closely than other European countries. After gas, in fact, the country exports to the EU mainly fertilizers, ammonia and hydrogen[5] , where it has more than 140 companies operating, as well as steel (where it has 7 main companies employing more than 3,000 workers), cement (where it employs 12,000 workers) and alumina[6] . These are all products that fall within the CBAM and for which Italy depends on foreign imports with price repercussions.

Countries such as Egypt, with a more diversified and integrated economy[7] or such as Morocco and Tunisia, may be less impacted as they specialize in different sectors, such as automotive manufacturing, food and beverages, and textiles. However, a future extension of mechanisms such as CBAM on other sectors cannot be ruled out, so assessing the effects of such a rule, both with respect to the immediate trade and cost impacts and on the actual contribution toward combating climate change is a necessary step.

The CBAM, in its current design, seems to have more the traits of a protectionist measure than a lever to promote industrial transformation in line with decarbonization in Europe and North African countries. North African countries, as things stand, may in fact have less access to the technologies and investments needed for decarbonization, and thus find it difficult to adapt quickly. Likewise, European producers would see increases in production costs with competitive repercussions, particularly for export-intensive countries such as Italy. For this reason, the implementation of the CBAM in a framework of regional cooperation and support that may also include the application of harmonization measures such as CO2 pricing mechanisms equivalent to the EU ETS should become a priority of the new EU Commission.

The Mediterranean area lends itself well to being a laboratory for new collaboration mechanisms for economic development based on reciprocity and synergy of action among the countries in the area. The Commission’s new mandate puts at the center of its action the challenge of Europe’s competitiveness in the perspective of decarbonization and adopts, for the first time, a privileged look towards the Mediterranean area with the appointment of a dedicated Commissioner. There is, therefore, an opportunity in assessing the consequences of unilateral mechanisms such as the CBAM and, potentially, modifying them to make them more effective toward achieving climate goals, not only in Europe, but by accelerating investment in ‘cleaner’ technologies in third countries as well.

–

[1] Emission Trading Scheme defined by European Directive 2003/87/EC

[2] In 2022, Algeria, Egypt and Libya traded about $50 billion worth of oil products and gas[2] . Italy re-exported about $3 billion worth of refined products to North African countries and Spain $1.8 billion.

[3] Values represent trade between the 5 North African countries and Italy, France, Spain, Greece and Turkey

[4] Economic values are always referred to 2022.

[5] It should be noted that hydrogen and ammonia are part of the value chain of fertilizers themselves.

[6] Data provided by the pan-Arab research center RCREEE in Cairo (Regional Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency).

[7] In fact, the country has 9 major companies in the steel sector, more than 9,000 chemical companies and more than 17,000 companies in the non-ferrous metals sector – Data provided by the UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organization) office in Cairo

House of Representatives:

Tuesday, December 17

Communications of the President of the Council of Ministers in view of the European Council on December 19 and 20, 2024

Thursday, December 19 / Friday, December 20

Continuation of consideration of motion Orlando and others No. 1-00374 on industrial policies.

Thursday, December 19 / Friday, December 20

Continuation of consideration of motions Richetti and others No. 1-00371 and Scutellà and others No. 1-00372 concerning initiatives to boost European competitiveness, in relation to the “Draghi Report”

By December 31

Approval of the budget law

Thursday, December 19 and Friday, December 20

European Council – link

At NetZero Milan, we firmly believe that emphasising the need for ambitious corporate climate action should not overshadow the challenges of maintaining competitiveness, to withstand the potential risks of deindustrialisation – in any case the need to move along pathways of just transition.

This is why we are committed to offering our participants, exhibitors and visitors an event that is not self-referential or celebratory. On the contrary, we do not want to lose sight of the value for money of the event and its true customer focus.