Issue #09

25 MARCH 2025

— Editorial by Alfredo Schweiger, Technical Director Federacciai, Federazione Imprese Siderurgiche Italiane

— INDUSTRIAL TRANSFORMATION POLICIES – THE CASE OF STEEL by ECCO

— KNOWLEDGE PARTNER’S TAKE – Decoding the Italian solar-plus-storage landscape by pv magazine and Green Horse Advisory

— KNOWLEDGE PARTNER’S TAKE – Energy storage gaining momentum in Italy by pv magazine and Green Horse Advisory

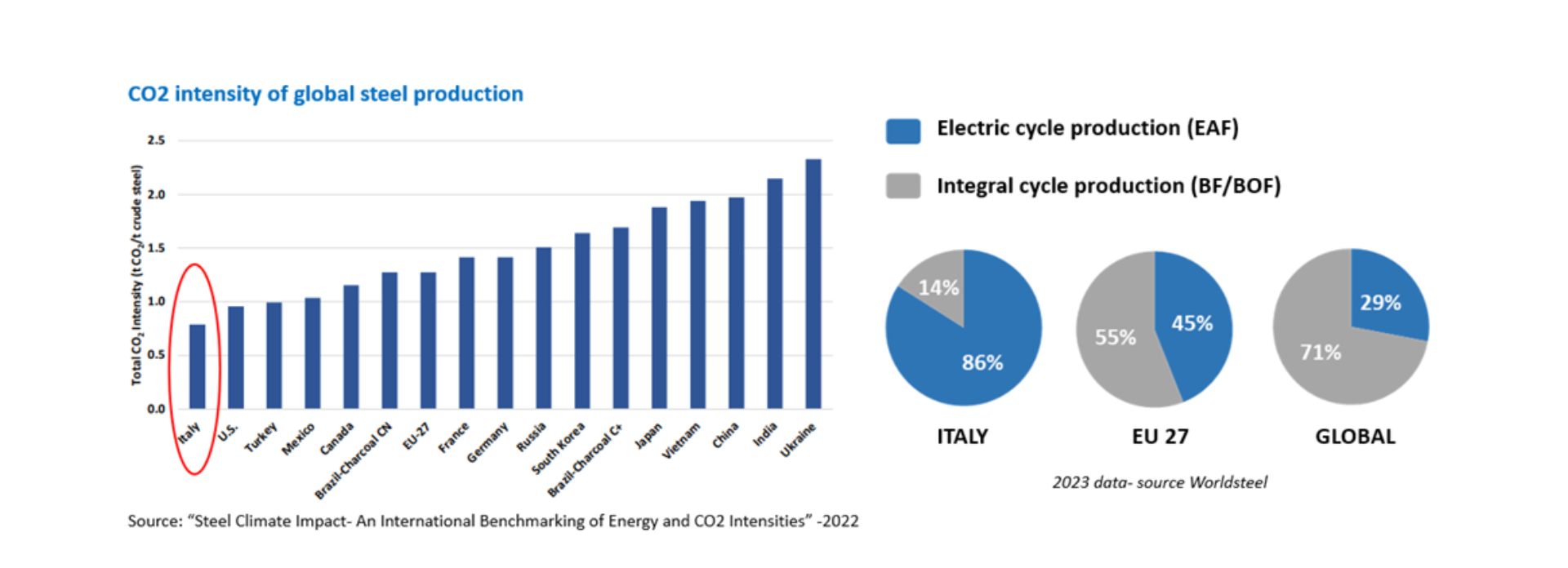

Since 1990, the Italian steel industry has reduced its CO2 emissions by over 60% and today boasts the lowest emissions intensity per tonne of steel produced in Europe, ranking among the first in the world for decarbonisation.

This achievement is largely due to Italy’s very high percentage of steel produced via electric arc furnace, a technology which recycles ferrous scrap and uses electricity for the smelting process. This results in lower emissions compared to the integrated steelmaking process, which uses iron ore and coal as raw materials. Other contributing factors include the high energy efficiency of Italian steel plants and the growing role of renewable energy in electricity consumption, progressively reducing indirect emissions.

The Italian iron and steel industry is therefore well-positioned to continue its journey towards climate neutrality, with the ambition of becoming a global benchmark in the coming years.

Leading Italian companies have launched ambitious programmes in this regard, involving the reduction of both direct (scope 1) and indirect (scope 2) emissions[1]. Furthermore, steel — a highly versatile and fully recyclable material — is recognised as strategic by European institutions, as it plays a crucial role in the implementation of key applications for the ecological transition. These include renewable energy and energy transmission networks; energy-efficient construction and infrastructure; sustainable mobility and railway transport; mechanics and machinery for technological transformation and automation; water collection and transport systems, etc.

However, the Italian and European steel sector, along with much of the manufacturing industry, is currently experiencing significant strain and declining competitiveness.

It is therefore urgent to ask: what are the essential conditions for a strategic sector like steel to continue and complete its decarbonisation process while maintaining competitiveness and profitability, which is crucial in today’s increasingly complex and challenging geopolitical context? Will the Clean Industrial Deal, recently presented by the European Commission, succeed in providing the missing piece of the Green Deal in terms of industrial policy and competitiveness—an aspect that has so far been largely overlooked by EU institutions?

Beyond the intentions outlined in the Steel and Metals Action Plan, recently published by the EU Commission, much will depend on the practicality of the actual measures put in place to address the following priority points.

Italian steel plants consistently face higher electricity prices, not only compared to global competitors, but also compared to competitors in other member states. Despite the increasing share of renewable energy in the national energy mix, electricity prices remain tied to fossil fuels such as natural gas (which has been subject to significant tensions and growing speculation in recent years) due to the so-called “marginal price” market mechanism. This system, used in Italy and other European countries, can prevent consumers (businesses and citizens) from benefiting from the reduced operational costs and the absence of carbon costs associated with renewable energy if it is not properly designed.

It is therefore crucial to urgently explore all possible solutions, ranging from targeted adjustments to the national model, to a broader European reform of market mechanisms aimed at lowering energy prices— in particular, enabling the decoupling of renewable energy prices from those of natural gas or other fossil fuels.

Different energy production mixes across member states, combined with the lack of a truly interconnected electricity system and the added burden of incentives left to national discretion in the form of state aid, have severely undermined the concept of a single European energy market, leading to significant competitiveness distortions. Therefore, it is necessary to standardise aid at the European level, including through common European funds, and to work towards the establishment of a single European electricity tariff for energy-intensive sectors exposed to international competition.

Technological plurality must also be ensured: all decarbonisation levers (not just renewable energy) must be considered and applied without ideological bias, selecting the most efficient and suitable solutions based on technical/economic criteria for energy-intensive sectors, which need a stable and continuous supply of decarbonised baseload energy.

Recycling just one tonne of ferrous scrap prevents the emission of one and a half tonnes of CO2, while drastically reducing the consumption of energy and natural resources. As the focus on low CO2 steel production grows in the EU and globally, demand for scrap will increase sharply. Globally, the share of production from electric arc furnaces, currently 29% of total production, could exceed 41% by 2030[2]. As global demand for scrap grows, it will likely exceed supply, risking a critical shortage that would particularly impact Italy, which already struggles to meet its needs through domestic collection. Ferrous scrap must therefore be classified as a strategic raw material for both circularity and decarbonisation, and as such, protected through measures aimed at increasing its availability and quality, but above all opposing its export (which has paradoxically increased in recent years) to countries that do not uphold the same environmental and social standards as the EU and lack comparable climate goals. Some of the areas where action is needed at the EU level include: regulation of critical and strategic raw materials; trade measures (export restrictions); implementation of the new regulation on transboundary shipments of waste; revision of the regulation on end-of-life vehicles.

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which works alongside the gradual phase-out of free ETS allowances for EU producers, risks becoming completely ineffective or even counterproductive if not thoroughly revised, simplified and integrated before it fully comes into effect in 2026. The recent simplifications proposed in the “omnibus package” fail to address the mechanism’s structural issues.

First of all, it is necessary to find suitable solutions to extend the CBAM to exports: without this adjustment, European products, burdened with rising CO2 costs, will be completely unable to compete in international markets. Additionally, the mechanism should be extended to include finished products made from semi-finished steel to prevent carbon leakage from shifting further down the supply chain, which would entirely undermine the purpose of the mechanism.

Finally, the CBAM’s operating mechanism has already proven itself to be overly complex and vulnerable, even during the transition phase. It must therefore be significantly simplified and strengthened, particularly to minimise the risk of circumvention and evasion by foreign producers. In any case, if the CBAM proves ineffective in addressing carbon leakage, the phase-out of free ETS allowances should be delayed, allowing businesses engaged in the transition to complete their decarbonisation journey without compromising competitiveness.

A harmonised definition of “green steel” appears more crucial than ever to make steel products with a lower climate impact easily recognisable on the market (based on robust and shared scientific criteria) and to effectively stimulate demand for low-carbon products. In this context, especially for strategic sectors like steel, European and national public procurement regulations (GPP – Green Public Procurement) should introduce mandatory minimum criteria or performance classes capable of driving public demand for “low-carbon” steel products (going beyond the simple approach of the most economically advantageous bid), while simultaneously awarding a premium to products Made in Europe, which must adhere to much stricter environmental standards and obligations than their non-EU competitors.

This should be achieved, as much as possible, through simplified application, using existing European standards to assess the environmental impact of products, enabling all levels of administration—from national to local—to apply them. To have a more significant impact in promoting demand for green steel, these criteria should also be gradually extended to private contracts.

As for a potential classification of “green steel” with relative labelling, this should be based simply on the actual carbon footprint (LCA – Cradle to Gate) using a technology-neutral approach. In contrast, any artificially constructed classification scheme on the so-called scrap ‘sliding scale’ (such as the recently developed “LESS – Low Emission Steel Standard” in Germany) is not acceptable. Such a system acts against the objectives of the EU’s circular economy, illogically discourages the use of ferrous scrap, and, most importantly, unfairly disadvantages the most sustainable steel production technology available today (electric arc furnace), a fully circular and electrified process that currently accounts for over 85% of Italy’s steel production.

[1] For further information see: Federacciai – Sustainability Report 2023

[2] “Shortfalls in scrap will challenge the steel industry” – Boston Consulting Group 2024

With the start of its new mandate, the Commission has prioritised reconciling its strategy for boosting competitiveness with the goal of decarbonisation. The Competitiveness Compass, published on 28 January, outlines the framework for this strategy, which involves reducing strategic dependencies and strengthening the link between competitiveness and decarbonisation.

In line with these principles, the Steel and Metals Action Plan was published on 19 March. This sector-specific plan, which focuses on steel and metals, falls within the framework of the Clean Industrial Deal (CID). Published last month, the CID outlines EU-wide actions needed to protect EU industry while advancing decarbonisation, through measures that address energy costs and strong international competitive pressure. The Steel and Metals Action Plan sets standards to support domestic demand for metals and scrap, while identifying enabling tools for the transition to green hydrogen. However, the EU strategy overlooks the opportunities for integration provided by the single market, failing to highlight the synergies and greater possibilities that would result from a stronger coordination of national strategies.

In this context, the upcoming presentation of Italy’s national industrial strategy[1], with the publication of the White Paper by the Ministry for Industry and Made In Italy, presents an additional opportunity to outline an industrial transformation plan that combines the safeguarding of competitiveness with the decarbonisation of the manufacturing sector, while effectively leveraging the benefits of integration within the single market at the level of individual supply chains, in which the governance of the Government’s project is framed.

This broad and diversified framework underscores the complexity of the current historical context in terms of safeguarding European competitiveness, which must also preserve the foundations of the European socio-economic model and the objectives of environmental and climate protection.

Steel is one of the most important sectors in Italian manufacturing: with an annual production of 21.1 million tonnes (2023), Italy is the second-largest steel producer in Europe and the eleventh-largest globally[2].

Steel plays a fundamental role in the national economy’s value chains. Due to its high level of specialisation in the mechanical industry, Italy is the second-largest steel consumer in Europe, with 23.5 million tonnes consumed in 2023. The main uses of steel in Italy are in construction (36.5%), followed by mechanics (20.2%), metal products (18.7%), the automotive sector (17.1%) and other sectors (7.5%). Long products are primarily used in the construction sector, while flat products are mainly utilised in the mechanical and automotive sectors.

To meet this demand, Italy heavily relies on imports, particularly of flat products, which recorded a net trade deficit of 6.5 million tonnes in 2023 (8.1 million tonnes in 2022). Italy is the world’s fourth-largest steel importer (by volume) but only the sixth-largest exporter. There is, therefore, a negative net steel trade balance of 2.6 million tonnes in 2023, a negative figure that has persisted for nine consecutive years and has been structurally increasing since 2014. When focusing on non-EU countries, the deficit has grown from just under 2 million tonnes to over 7 million tonnes in 2023.

One factor contributing to this negative balance is the significant decline in Italy’s primary steel industry (steel production from ore) over the past decade, with the number of direct employees falling from 36,000 to fewer than 31,000 (-15.5%). The only plant currently active on a national scale that produces steel from ore is the former ILVA site, whose production continued to decline even in 2024, reaching a historic low of just over 2 million tonnes[3]. Despite this, Italy is Europe’s leading producer of Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) steel. 86% of the country’s total steel production is derived from recycled steel scrap, therefore, from recovered materials, which results in lower energy consumption and emissions per unit of production. As a result, Italy’s steel production is among the most efficient globally, with significantly lower emissions per tonne of crude product compared to steel produced from ore using coal-based Blast Furnace-Basic Oxygen Furnace (BF-BOF) technology (BF-BOF processes emit approximately 2.3–2.5 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of steel, whereas EAF technology emits only around 0.08–0.09 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of steel).

Steel production is one of the sectors most exposed to global competition, given the high impact of energy costs on the final product price, in a context where European energy costs remain significantly higher than those of international competitors. Additionally, the global steel industry faces an estimated global overcapacity of over 611 million tonnes (2023), with projections indicating a further increase of 124 million tonnes between 2024 and 2026. Most of this additional capacity will be concentrated in India and based on the BF-BOF process, while production in other parts of the world is increasingly shifting towards electric furnaces[4].

Moreover, the recent decision by the United States on 12 March, 2025, to impose a 25% tariff on steel and aluminium imports is expected to negatively impact EU producers, limiting access to the US market, including for base metals transformed into downstream products. This will also increase pressure from exports that were previously destined for the US, which may be redirected to the EU market.

In such a complex international landscape, the European decarbonisation process plays an important role in understanding how to revive the competitiveness of the Italian steel industry. On the one hand, by aiming to create dedicated markets for ‘green’ products, where Italy’s low-emission steel production could provide a significant competitive advantage. On the other hand, by intervening to reduce high electric energy costs, which in Italy, for example, are burdened by particularly high fiscal and parafiscal charges.

In the context of implementing European decarbonisation and competitiveness policies, there is a clear need for an integrated policy approach to support the steel sector’s transition, considering the entire supply chain and the broader implications for the energy, economic and social systems. Relying solely on the implementation of ‘technologically neutral’ policies, such as the EU ETS, cannot be insufficient to effectively accompany the transition[5].

The industrial strategies of major global economies consist of closely integrated policy packages that combine fiscal policies to support domestic production, trade policies to penalise anti-competitive practices, and foreign economic policies to secure supply chains.

Therefore, it is necessary to design a set of industrial policies with different levels of priority and coordinated execution, as proposed in the study Policies for industrial transformation – the case of steel[6].

Supply-side support policies should target investment costs while also stimulating domestic demand for enabling technologies, many of which are produced in Italy and across Europe. To tackle high energy costs, it is necessary to implement policies that ensure stable and competitive electricity prices, such as contracts for difference (CfD) and Power Purchase Agreements (PPA), and to incentivise the growth and penetration of renewables into the electricity system at competitive prices, as highlighted in the Action Plan for Affordable Energy recently published by the Commission. Technologically neutral measures, such as the EU ETS that disincentivise high-emission processes, can contribute to decarbonisation but are not sufficient on their own. These risk becoming punitive if not accompanied by initiatives that incentivise low-emission alternatives, which should focus on the most cost-effective technology— electrification.

At the same time, it is essential to introduce incentive and protection mechanisms on the demand side to promote the development of a market that can accommodate the more expensive ‘green’ steel production, for the market segments where this is necessary. The higher costs of ‘green’ steel are, in fact, ‘diluted’ in high-value productions of which steel is only one component. Therefore, it is essential to carefully assess the cost and benefit of introducing standards or markets to promote specific products. It is also necessary to ensure clarity in the definition of ‘green’ steel, and for the upcoming proposals for standards in this area to follow an approach of proportionality and relevance in relation to the emission contribution of various production stages, while properly considering recycled content.

Mechanisms to support demand must also be devised for the production of secondary steel from ferrous scrap. Despite the lower emissions of scrap-based production, the volume of scrap used in the EU is declining due to two factors: low domestic demand and high prices, often driven by foreign demand sustained by unfair trade practices or subsidies (see ‘A European Steel and Metals Action Plan’). Establishing minimum standards for recycled content in products using steel, along with trade defence tools, can help address the current challenges related to the cost of ferrous scrap.

In a time of global competitive tension, like the present, measures to protect the most efficient productions at the EU level must also be ensured. In this regard, the expected revision of the Carbon Border Adjustment Measure is welcomed. However, the complexity of implementing the mechanism and the potential for circumventing the regulation raises concerns, especially for metal transformation supply chains.

A coordinated action at both the European and national levels is needed. If the European industry collectively moves towards closing the innovation and productivity gap, effective action can be taken. In this regard, the development of both national and European strategies represents an opportunity that should not be missed. European action would benefit from a greater contribution and coordination of national perspectives: at this level, the interdependencies and synergies of production systems are more evident. European strategies can only be effective if they are based on the common and complementary needs of individual nations, considering the economic and production fabric of each, in order to fully maximise the benefits of the single market.

[1] “Made in Italy 2030 – Green paper for a new industrial policy strategy for Italy” MIMIT (2024) https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/libro-verde

[2] Worldsteel (2024), World Steel in Figures 2024, World-Steel-in-Figures-2024.pdf

[3] Ex Ilva, nel 2024 produzione a picco – Corriere di Taranto

[5] Technology-neutral vs Technology-specific Policies in Climate Regulation: The Case for CO2 Emission Standard

[6] Draghi report, 2024 https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

At the upcoming NetZero event organised by Fiera Milano, pv magazine and Green Horse Advisory will jointly host two vertical sessions on the development of PV and battery storage businesses in the Italian energy scenario. Both national and international speakers will explain the challenges and opportunities facing investors, developers and energy-intensive businesses in their decarbonisation efforts, with discussions also focusing on the role of technologies and prices across investment paths.

According to the Integrated National Plan for Energy and Climate Change (PNIEC), Italy should add an additional 50+ GW of solar power by 2030. The country’s solar capacity stood at 37.08 GW at the end of last year, following growth of around 7 GW in 2024. The country should now install 10 GW a year until 2030 to meet this target.

This challenging task will require all stakeholders to gain extensive knowledge of the global PV supply chain and understand the geopolitical and economic dynamics behind it. The PV manufacturing industry is not only going through another consolidation cycle, but is also experiencing technological shifts, with new cell and module architectures likely to destabilize the current tech scenario.

With manufacturing costs going down and module prices now experiencing a long-awaited upward trend, understanding cell and module technologies is key to the search for the best products at the lowest price, for both rooftop and ground-mounted PV systems. The European Commission is seeking to support domestic PV manufacturers, which means a newly subsidized solar industry may soon see the light in the Old Continent, with developers and investors being required to assess the quality and price of solar products made in the EU.

Despite geopolitical turmoil and a change in priorities at the both the European and global level, the case for solar installations remains very strong in Italy, as solar PV remains the country’s cheapest source of energy.

Recent policies changes have not deterred investments in solar projects in Italy, as many installations are ready-to-build, and a new support scheme – the FerX – is expected to boost business, particularly in Italy’s southern regions, despite additional regional premiums. Meanwhile, installations in the North should be propelled by a rise in power purchase agreements (PPAs), which allow for mitigation of geopolitically driven oscillations in energy prices. These schemes are expected to drive the development of the market through to the end of this year, before contributing to even more pronounced growth at the beginning of 2026.

Several challenges, however, still need to be addressed. High inflation, interest rates and installation costs represent an increasing share of project costs continue to impact C&I solar installers and EPC contractors. Question marks also remain around if developers can fulfil the demand for new projects due to difficulties in overcoming legislative developments, local resistance and difficult financing scenarios.

As more and more installed PV capacity comes online, energy storage enters the picture as another pillar of Italy’s energy transition, especially after the government defined the new Macse auction mechanism for large-scale batteries. With this in mind, and as the business case for storage projects linked to rooftop PV becomes increasingly strong, installers and EPCs are now busy identifying the best technology providers and optimum battery designs to make projects bankable, regardless of their size.

Understanding new legislative frameworks, as well as the current discussions on how to improve provisions for all types of storage systems, will be key to helping investors and developers secure permits and financing, especially as pumped hydro and other mechanical technologies, such as compressed air, may increase competition in an environment that could soon become rather crowded.

At the upcoming NetZero event organised by Fiera Milano, pv magazine and Green Horse Advisory will jointly host two vertical sessions on the development of PV and battery storage businesses in the Italian energy scenario. Both national and international speakers will explain the challenges and opportunities facing investors, developers and energy-intensive businesses in their decarbonisation efforts, with discussions also focusing on the role of technologies and prices across investment paths.

Italy’s decarbonization plans rely heavily on renewable energy, particularly wind and solar, and require large-scale daily and seasonal storage systems. In recent years, research on storage has accelerated, backed by increased funding, and the global energy storage market nearly tripled in 2023.

The European Commission recently approved a €17.7 billion ($19.2 billion) Italian plan under EU State aid rules to support the construction and operation of a centralized electricity storage system. Italy’s proposal includes facilities with a combined capacity of more than 9 GW/71 GWh.

As the energy sector works toward these goals, the supply chain is securing the best technologies and prices amid uncertainty over which solutions will dominate. While lithium-ion batteries lead the market, sodium-sulfur and flow batteries are gaining interest from researchers and industry players. Mechanical technologies, including gravitational storage, compressed air, pumped hydro, and flywheels, are also positioning themselves in an increasingly competitive landscape.

Pumped hydro, already well established in Italy, could emerge as a key competitor to lithium-ion systems. The European Union has 44 GW of pumped hydro capacity, accounting for a quarter of global installations. European hydro basins provide 220 TWh of storage capacity.

For short-term storage, lithium-ion technology will remain dominant, with some alternative technologies playing a marginal role if properly subsidized or valued.

Long-duration storage (LDES) presents a different outlook. There is no universal definition of its time frame, though many consider it to be under 24 hours. Most LDES alternatives to hydroelectric storage remain in early development and have variable costs, but some are already cost-competitive with lithium for extended storage periods.

The unit costs of many LDES solutions decrease as project size increases, making them more scalable than lithium-ion systems, where costs rise in a more linear fashion, limiting the viability of adding more operational hours.

The development of energy exchange networks, such as those in energy communities, will also expand the availability of distributed storage. However, this requires investment in new technologies and long-term policy planning. These networks could become fully operational by 2030, with further optimization through 2050.

Italy’s Integrated National Plan for Energy and Climate (PNIEC) calls for a significant increase in storage capacity to balance the intermittency of renewables, targeting between 6 GWh and 8 GWh by 2030.

By 2050, forecasts suggest storage capacity will need to exceed 20 GWh to support an electricity grid dominated by renewables. The integration of electric vehicles into the grid, using technologies such as vehicle-to-grid (V2G), could reduce reliance on traditional storage by 2040, stabilizing the grid during demand fluctuations.

pv magazine and Green Horse Advisory are confident their two vertical sessions at NetZero Milan, organized by FieraMilano, will shed light on all the critical issues discussed above, with experts from academia, industry, finance and the PV sector set to provide deep insights into the depths of the energy transition.

Wednesday, March 26

Review of the Commission’s communication to the European Parliament: The road to the next multiannual financial framework

Thursday, March 27

Informal meeting with the European Commissioner for Budget, Anti-Fraud and Public Administration, Piotr Serafin, on the next Multiannual Financial Framework

Upcoming issues to be discussed in Parliament:

– Examination of the European Commission’s Work Program for 2025

– Examination of the institutional aspects of the European Union’s trade strategy

Tuesday, April 8

Road to NetZero Milan Webinar: ELECTROCHEMICAL ACCUMULATORS FOR INDUSTRY AND THE POWER GRID link

Thursday, March 27

Environment Council (ENVI). Discussion on the environmental aspects of the Clean Industrial Deal – link

Monday, April 7

Foreign Affairs Council (Trade) – link

Friday, April 11

Eurogroup – link

Friday, April 11 and Saturday, April 12

Informal meeting of the EU Ministers for Economic and Financial Affairs and Central Bank Governors (ECOFIN) – link

Monday, April 14

Foreign Affairs Council – link

Tuesday, March 25 and Wednesday, March 26

Petersberg Climate Dialogue (Berlin, Germany)